When we constructed the geometric algebra of space we proved that the square of a unit bivector ![]() (the oriented unit of area) is -1 and so is the square of the unit volume: the trivector

(the oriented unit of area) is -1 and so is the square of the unit volume: the trivector ![]()

It’s really a surprising result: go and explain in simple words how it is possible that the square of a tangible geometric entity is worth a negative number! For now we must stop here, just remember that the concept of orientation is very important. In fact, in geometric algebra it is not enough to define the area as a geometric entity: the sign is fundamental.

At this point it’s very strong the temptation to ask ourselves:

does the unitary bivector ![]() identify itself with the imaginary unit

identify itself with the imaginary unit ![]() of complex numbers? So what about the unit trivector

of complex numbers? So what about the unit trivector ![]() ?

?

if the square of both is -1, do they represent the same imaginary unit?

These are legitimate questions, but some caution is needed here.

First, the good news.

We can hardly contain the satisfaction of finally seeing that the imaginary unit ![]() has a body and a behavior.

has a body and a behavior.

We say body to indicate that ![]() is no longer a ghostly entity, so abstract as to be non-existent: we have it in front of our eyes and it has been so for centuries, before the eyes of mathematicians.

is no longer a ghostly entity, so abstract as to be non-existent: we have it in front of our eyes and it has been so for centuries, before the eyes of mathematicians.

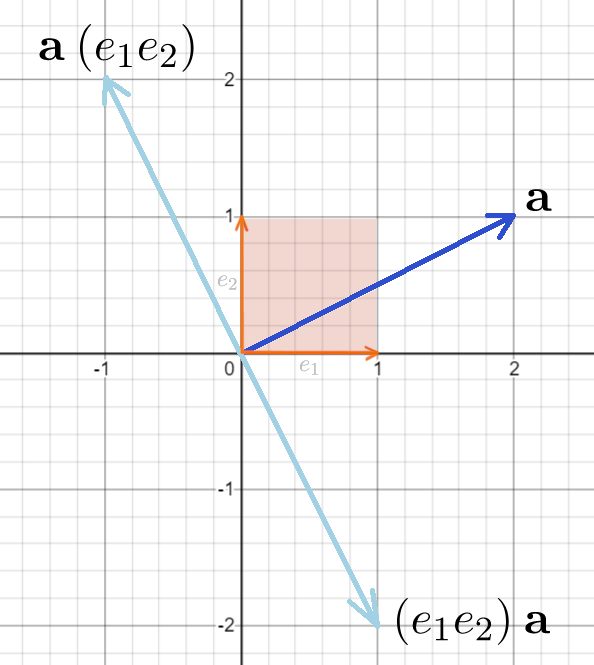

The imaginary unit must be identified with the unitary portion of the bivector. It’s an oriented piece of the plane. We say behavior because it is even more interesting to see its effect on other geometric entities. Let’s try to play around with it using a generic vector as test body, which we will multiply by ![]() first on the right and then on the left:

first on the right and then on the left:

![]()

![]()

![]()

So multiplying right by ![]() (which is a counterclockwise oriented bivector) causes

(which is a counterclockwise oriented bivector) causes ![]() to rotate counterclockwise, while multiplying left reverses the direction of rotation. From this point of view the bivector

to rotate counterclockwise, while multiplying left reverses the direction of rotation. From this point of view the bivector ![]() differs from

differs from ![]() because it does not commute, rather anticommutes with vectors.

because it does not commute, rather anticommutes with vectors.

Warning: we are used to seeing the operator that “attacks” its operand from the left, but in this case it is the operation from the right that preserves the orientation!

As we mentioned before, we underline a very interesting duality: each element of the GA can be seen as an object but also as a operator . At school, complex numbers are seen almost exclusively as objects, statically fixed in the Argand-Gauss plane as Cartesian points. In the GA, on the other hand, they acquire an active dimension, becoming rotodilation operators.

A second meaning sees them as duality operators, which transform elements of the algebra ![]() of degree

of degree ![]() into mirror elements of degree

into mirror elements of degree ![]() .

.

The bad news is that we can’t identify four distinct concepts, even if algebraically they behave similarly:

- the unit 2D bivector 2D

- the three 3D unit bivectors

,

,  ,

,

- the unit 3D trivector

- the imaginary unit

of complex numbers

of complex numbers

All of these elements square to -1, but that’s not enough to say they’re the same thing. In fact, it is necessary to consider the commutativity, which is valid for ![]() and for the trivector

and for the trivector ![]() , but not valid for the bivectors.

, but not valid for the bivectors.

We will therefore have to use distinct symbols and therefore we will keep the ![]() for the imaginary unit, while we will use

for the imaginary unit, while we will use ![]() for the 3D trivector, since the properties coincide. Sometimes

for the 3D trivector, since the properties coincide. Sometimes ![]() is also used for the 2D bivector, but if the context is not clear, the symbols

is also used for the 2D bivector, but if the context is not clear, the symbols ![]() or

or ![]() could be used.

could be used.

Widely used for historical reasons too the ![]() from the electrical world (being

from the electrical world (being ![]() reserved for the current!).

reserved for the current!).